For people who don’t know you, could you tell us just a little bit about your background and how you ended up in in the Frozen Midwest?

I’m originally from Southern California which is not frozen, and I spent my formative years out there studying and working in the LA theater circuit. Mostly waiver houses, storefront companies, a few local touring companies, a children’s theater, one national one…it wasn’t a Broadway company but it was it was housed out of LA. Occasionally had directing gigs mostly by Invitation with companies that I found a home with and then after serving as company manager with one for five years, because actor salaries aren’t so steady, I was accepted in grad school in New York City and it was there that I…in California I was interested in acting obviously as a profession but had also gained a certain amount of interest in it as a theoretical pursuit. At that time, late 80s early 90s, just beginning to get interested in the idea of: could…can you really teach acting or is it kind of this Guru kind of thing that just happens, or it doesn’t, right? And I was in that camp that said no, really. What we would loosely call the American school of Method Acting, is based on Behavioralism basically, um, uh, Dialectical Behavioral Theory. And you can actually use that soft science to break down components and teach it; anyway, not here or there, but that was one of my interests and which is why I went to grad school, anyway, to pursue that. But when I was out there, I really began to understand the how and why of the truly exceptional directors and producers I’d worked with in LA. What made them different than, well, the others that aren’t so different. I began teaching in the early 1990s first in LA and and then in Saint Cloud State, that was my next gig. I eventually ended up as chair of the Theater at Anderson University. So what brought me to the chilly Midwest? Work. That’s what brought me to the chilly Midwest. While I was at Anderson, we developed a model professional company that was financially independent of the school. This is pretty common with graduate programs, it’s how they get their MFA students to earn Equity points or actually get their Equity card. It was fairly unheard of at that point for undergraduates so it was kind of pioneering if I can brag a little bit. And we would produce both locally up there in Madison County, not only just at the University, but at other venues. And we would produce down here in Indianapolis. And we developed this kind of, uh, best way I could describe it is like a lend-lease arrangement between ourselves, Theater on the Square, which is what the District Theater used to be called, and Shawnee Summer Theater. Obviously, the Shawnee, being summer theater, they didn’t need any of their equipment during the school year. I didn’t need my equipment during the summer, and back in those days Theater on the Square virtually had no equipment. So it worked very nicely that during the school year I would have Shawnee’s equipment. I could loan it, with their full knowledge, I could loan it to Theater on the Square in exchange for – each semester, so twice a year – one week of rehearsal and two weeks of performance.

The idea was to create a company whereby we could connect emerging artists, which would be our seniors – but not just ours, any senior that we could funnel in – so emerging artists with established artists, be that actors, or designers, or stage managers…do a lot of work with connecting directors because undergraduate school. And [it] just worked out just wonderfully for us. Unfortunately, the university decided to eliminate the theater program, and because the Company was financially independent of the University, I took the Company permanently here to Indy and we became the resident company for the for the Fringe Theater at the time.

And there, with the help of Amy Gaither and Callie Burke, who are my co-artistic directors, and just a long list of connections we’d made over the five to seven years we had been working as this model Company, Wisdom Tooth Theater Project produced some wonderful work that I’m still really proud of to this day. World premiere of Jason (and Medea), but the Indiana premieres of a lot of well-known plays: The Last Days of Judas Iscariot, Water by the Spoonful, Lisa Loomer’s, one of my favorite West Coast playwrights, Distracted, Living Out. We were the first company in the state to produce Almost, Maine and Impressionism, just a lot of wonderful stuff. And we kept that vision. not only [to] have a professional scale of actor but always room for the newcomer. And I won’t name any names but there are two very, very, popular actors in this town that have their Equity card now and they got their first production with Wisdom Tooth.

So then I decided to slow down, as you do when you get into your late 50s and early 60s, and Amy moved to New York and she produced there. She has had a wonderful article written about her about a year or two ago in American Theater Magazine with a show that she produced up and down the East Coast. Callie runs Betty Rage Productions now, focusing on female-forward work and I am a freelance actor and director chatting with you today.

You mentioned that you got your start in Southern California working in waiver houses…can you explain what a waiver house is?

I’m not sure Equity still does this but at the time, which would be the late 70s moving into the 80s – I went to New York in’ 91 – if a house had 99 seats or less and they wanted a LORT contract – LORT is the League of Resident Theaters – so if they want to employ an Equity actor they have to pay them scale, which at the time I think was about $600 a week. Well these little theaters that they couldn’t be paying five or six actors $600 a week, there’s just no way. So, if they had less than 100 seats – 99 seats – they got what was called a waiver, and so they could pay the Equity actors less. And at that time it was contracted between the actor and the company. There had to be some money exchanged but it could be…(laughs)… it could be pretty dismal. Frankly I remember plenty of 150-dollar weeks. But that’s what a waiver house is. I’m not sure Equity still uses that terminology or even still has that out for actors anymore.

You mentioned you went to grad school in New York City…where was that?

City University of New York, and the reason I went to City University is because at my heart I’m a socialist cultural materialist and that is a school that was free. Not exactly free but pretty much free if you were a resident of New York City. It was a service of the city to its population where you could go from the Bachelor’s level to the PhD level and all you were paying for was class fees and books. Now my first year, since I was from LA, I was paying full tuition. After that, my second year I paid 500 dollars to go to school there. I was able to get through…I never finished my PhD…I never passed my language exam so I don’t want to present myself as a doctor when I’m not, but I was able because of that to go through bachelor’s, two masters, an ABD (All But Dissertation) on a Doctoral degree for 500 dollars a year in New York City, how crazy is that? And the great thing about City University is they had a great agreement…this is where the lend-lease idea I got that I brought to Anderson…I could take classes at NYU, I could take classes at Columbia for no more tuition. They would allow me to attend those classes for no more tuition. One of my graduate advisors on my dissertation was from NYU so it was, it was wonderful, it was wonderful! Frustrating that these opportunities don’t exist anymore.

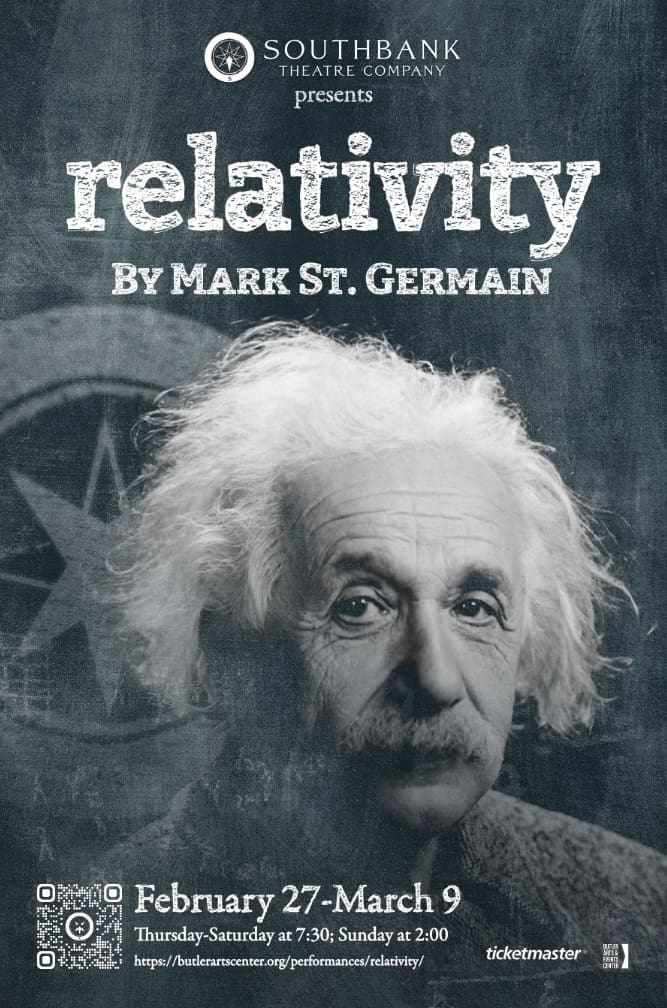

Can you talk about how you came to direct Relativity at Southbank? What drew you to the play and also drew you to Southbank?

Yeah. Mostly when you’re freelance and you have a bit of, a bit of a career behind you, you get picky.

For example I don’t just want to direct, I don’t want to get really esoteric, I don’t want to direct, say, Equivocation, which is a wonderful play. I want to create a work of art that’s very specific to this audience, this time, this place, through collaboration with other artists. With designers, stage managers, actors who also believe working collaboratively produces better work. And you have to find a company that you believe will get on board with that. And sure, who wouldn’t? But a company has to have the means to do it, which is a financial question. The company has to have enough of a reputation that it can pull in actors and designers and directors to its auditions to be able to execute something like that, and it has to have the culture to do it, right? I mean we can go back into the history of the, you know, the artistic director and then emerges the managing director, and then emerges the producing artistic director, and how the culture of regional theater, you know, shifts around from “let’s do art” to “let’s make sure we can pay our artists enough to make rent,” right, so it’s all over real and living thing.

So you know, and in a town like this I mean, what, there’s half a handful of LORT houses in town, professional houses, and a few universities around here that still have a budget, right. The directors are often lucky to get just pocket change not only in compensation for the work; they’re lucky to get pocket change in order to execute their vision and that that’s a critical issue. A critical issue.

So I see shows and I watch what companies produce, and I pay attention, and I’ve been watching…well, the first Southbank show I saw was the musical, Twelfth Night they did, which I thoroughly enjoyed, and I’ve been watching Southbank ever since. And so when they secured a home at the Shelton [Auditorium], which is a very well appointed space, so now the means begins to step up of what you’re able to execute. And they started putting out a call for directors for Relativity, I sent them a pitch, and luckily, they accepted my pitch, and in a few weeks we’ll see how wise a decision that was. I’ve directed actually two of Mark Saint-Germain’s shows previously, and I was a week from starting rehearsals on a third when the production got canceled. I like his stories. I mean it’s as simple as that. I like his stories. I like that he’s got a very honest way of handling sentimentality, which I can enjoy. I don’t always like his dialogue. Sometimes I…I sometimes I think he gets lazy verbally and it lets his characters drift into stereotype which is always a danger when you’re…when you’re playing in the world of sentiment, but obviously considering my history as a director, I like his stories, uh, more than I’m critical of his dialogue. So that’s…that’s what brought me to Southbank and to this show. Stories and a company that I thought could get on board with “let’s do good theater.”

I’d like to talk to you more about what your process was: how you arrived at your casting choices, and your approach. Can you talk a bit about Unified Production Concept, which I understand is the basis of your training?

Cool, just to hit it right out of the gate. So anyone who’s, you know, had to sit through a Theater History class, may or may not remember the Unified Production Concept. That’s from the turn of the last century. Saxe-Meiningen, Stanislavski…all that turn of the century theater. We start really getting into realism and how…the direction that realism can push us into. Because you know Unified Production Concept can go past that, but you need to get there before you can even go into some of the work past that. But basically at its root it’s a recognition that the script, the design, staging, the character development, the lights, everything should all be in fact singular, unified, one. Unified so it all comes together into this one piece, it’s coherent, you don’t have things floating around you don’t understand, and it’s collaborative. A number of artists have worked together on the singular vision to produce this one particular piece. So, for example, a few years back, probably getting close to 10 years now, I saw [a] wonderful production. It had the most…just an amazing set, and actually quite a small space, and it’s set just seemed to…just seemed to kind of meander towards the heavens. It was clearly directional, and yet it almost lacked a sense of force and will. It was just wonderful, and as I’m telling you this I don’t even remember what show it was because the set wasn’t unified with anything else. I came out of the show humming the SET instead of the songs or whatever it was. And that’s…that’s an example of that. And, and part of that just comes with the nature of where we are economically in theater. Even before I left AU we were dealing with what I like to, I don’t like to call it, but what I call mail order set design, and mail order lighting design. They will send you, if you send them a CAD drawing of your space with all your lighting positions, and they send you a CAD drawing back of your set. And they send you a CAD drawing back of your lights and they’ve never even been in the space. The lighting designer has never even seen the set that they’re designing on. And it’s…it’s just the economic reality of; a designer has to be able to work nationally in order to make a living. And companies don’t have the money to have a resident lighting designer. But part of the limitation, that is, is you start getting shows that have that feeling of kind of being snapped together and I really, really struggle to try to get away from that.

So what I might start with…so if a piece catches my attention, or is brought to me in this case by a producer, I’m going to read it through once, just once, and I’m going to set it aside and mull over it for at least a week.

And this is as close as I think I’m going to get to how an audience is going to experience seeing the show produced, what I might call straight. Or seeing it how they’re going…what is this show saying on its on its face, right? What are they going to take away? What are they going to be thinking about the next day? What is this play saying directly?

And then when I think I’ve landed on that then comes the closer readings beyond the face value. What’s at the heart, what’s at the soul of this play, you know?

For example, in this show Einstein has a line, he says, “Everyone has genius, but if you judge a fish by its ability to fly it will spend its whole life thinking it’s stupid.” Lovely line. Now, does this line just function on its face? Is it telling us something about how Einstein thinks and little insight he wants to hand out? Or is it gesturing at how the characters are missing a connection because one is flying, and the other is swimming? And is it an insight into one character, into both characters, is it insight into the scene, of the whole act, the whole play? You start looking for your cues.

Now, once I understand the story and the theme that the play, what the soul of the play wants to tell, then I look for clues to help me understand what scenic elements, lights, sets, costumes, etc., is going to best enable and forward that story and theme.

So I’m interested in working with a play in relationship to THIS PLACE. What does Relativity mean in Indianapolis? This time. What does Relativity mean in 2025. And in this context. And the context I see dominantly, that can be addressed by the place. We live in this absolutely binary chasm, and who and what we choose to idolize at this moment. No one is on the fence about Vice President Harris. You like her or you don’t. No one is middle ground on Donald Trump. You like him or you don’t. It’s a chasm, right? Anyway, so once I’ve landed on this, kind of aesthetic core, this becomes the starting point from where all the designers, performers, and myself, well now it’s just…it’s not the final conceptualization. It’s a compass point. It’s the True North of the play that we’re going to aesthetically navigate by.

That being said, the set of Relativity, which is set in a study, is not interchangeable with Freud’s Last Session, which is also set in a study. Because this study has to emerge from this unique and collaborative production. And then everything that’s embodied in this collaboration, this research, this work we do together, has to flow effortlessly through the original story, characters, the original ideas you came away with from that very first reading, otherwise you come out with this amazing set and you don’t even remember what play you went to see, right? The work becomes distorted.

So let’s get a specific example from Relativity. On its face Relativity uses Einstein as a foil to explore the idea of what makes a great man. So, Einstein thrives in this world of problems and solutions, of convoluted ideas, esoteric imagination, and he only exists in our world, our world of coffee shop conversations, and Thanksgiving dinners with the family, via this very carefully constructed persona of clever quotes all wrapped up as the frumpy absent-minded Professor. Because that’s how we can digest him. So, Einstein’s identity is in his work, in his formulas. It made him a world figure and in the disguise he gets to wear. Now Margaret, who is the reporter who has come to do a story on him, her identity comes from the family that believed in her and nurtured her. A father specifically, who she knew to be a good man. And she wants to write a different kind of story. She wants to write about the Einstein that no one knows, right, the Einstein who is a husband and a father. The Einstein who had parents, from the family aspect, because that’s her world, right? And she’s hoping to find this good man within this mostly untold story about Einstein as a family person. Now to reach this Einstein, this good man within the great man, that her article wants to find, Margaret has to navigate through his persona, which here is going to be represented via an actual cluttered set, and actual frumpy clothing, past his world of ideas and Imagination, which is going to be represented through more presentational scenic elements and… come see the show because I’m not going to spoil it for you… before she can actually reach the man. The man she wants to find. So, there’s a lot more going on here than two people talking in a study. I mean that story I could read.

So how does this…how do we make a show with all this blah, blah, blah I just said? So, we started with the idea of the story literally being played out on a cluttered stack of Einstein’s notes and papers. And this has evolved as I chatted with the designers, connected with the vision that we originally came to, to his point where the setting, lightning, scenic design, all of that evokes not a cluttered office, but his idea-scape. She has to navigate through his world of ideas.

Now, though I’ve talked a lot about production elements, actually I think of myself more of an actor’s director. You can interview the actors to explore that, but to let you know about the facts, so I’ve talked a lot about design, but what actors have to say about this. Two days ago one of the actors told me in the last scene, “Well, this is what I see happening.” Which is not what I had seen happening. And I thought, “Wow, yeah, that changes how the lights and how the sound has to close the show.” All right, you know I’m not going to, you know, her, her idea was…was…was…was “right” or “good,” I mean it’s a value judgment. But her idea was better than what I was going to do, so between the two of us…and now we get to join in the sound design, and now we get to join in – and actually is going to affect how part of the set is painted, actually down to that detail, right? So, an idea that this actor said, “This is how I think…this is what I think is happening in these last moments.” And it’s like, that actually changes some of how this production is going to go together. And that’s what I mean by collaboration. Rather than saying, “Well, that’s an interesting idea but I want you to play it this way because the set’s not going to do that for you.” Yeah, you make the change, right, because as a group of artists working together we become, we arrive at a bigger picture, at a better work than we would individually.

Wow, I just talked a lot there, didn’t I?

I think the question I’d like to end on is: what would you like the audience to take away from the play?

Yeah. So what is at the soul of this play that we want to get through on face value? It’s…it’s hard when our heroes don’t live up to their hype, or, or more accurately it’s hard when our heroes don’t live up to the hype we invest them with. When a figure like Albert, or even just a big sister or parent isn’t the “fish” we wanted or needed, we often respond in a very binary fashion, right? When our great person wasn’t a great parent we either ignore or excuse their failings. “Well, they loved us the best they knew how.” That’s the one I hear a lot. Or we become angry and condemning of the disillusionment that I have put them out of my life. See, the binaries, right? So, how we detach our sense of self and self-worth from how we idealize these figures in our life – and we all have figures in our life that we do that with…they don’t have to be famous. So, how we grow through them, how we grow beyond them, how we hold them accountable, how we forgive them. This struggle between Margaret and her great man, between this “fish” and this “bird,” I want the audience to take away that story of learning to detach our value from our admiration.

Is there anything you would like to add in the couple of minutes that we have left?

I would love it if people would come see the show I just chatted on about. We open February 27th, that’s a Thursday and we run Thursday, Friday, Saturday at 7:30 and then Sunday at 2, and then the next week which is March 6 through 9, right, Thursday, Friday, Saturday, at 7:30 and Sunday at 2. Come to see the show. The rehearsals are going wonderfully. I’m just excited the cast is now becoming the expert on the show and the collaborative work is just…I’ve had my third meeting with the set designer and said listen, this last bit we have to change, and this piece needs to be repainted to cover this other thing, so this is really kind of the exciting part of the work when you start saying, “Man, I never would have thought of that, but of course! There it is!”

Come see Relativity at Shelton Auditorium (1000 W 42nd Street, Indianapolis at Butler University), Thursday-Sunday, February 27 through March 9. Tickets at the door (cheaper!) or online at https://www.butlerartscenter.org/performances/relativity/. You can also visit the Clowes Hall Box Office Wednesday-Friday from 10am-4pm if you’d prefer to purchase advance tickets at door prices (After venue fees, the prices at the door or Clowes Box Office are $29 general admission, $24 students/seniors/military).

Share :